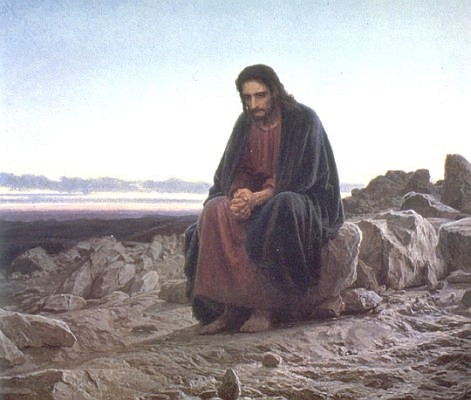

Christ in the Wilderness- Ivan Kramskoy- 1872

Christ in the Wilderness- Ivan Kramskoy- 1872

This is part three of a series on Lent. Part one: On the Origins of Lent; Part two: The History of Lenten Fasting.

Fasting is a biblical practice. In the sermon on the mount Jesus denounces the false fasts of the Pharisees, yet he assumes that fasting will nevertheless be a part of the Christian life. Twice in Matthew 6:16,17 Jesus says, “When you fast.” That Christians should fast is assumed by our Lord.

Despite this clear biblical teaching, while I’ve heard a great deal from Reformed teachers concerning when we shouldn’t fast and what fasting isn’t about, I’ve heard scarcely little written in a positive fashion about when and how we should fast. Now, what the recent teaching on fasting has done well is to offer a corrective to the idea that fasting is some sort of spiritual discipline. Fasting is not a spiritual discipline. In the Bible, fasting is always accompanied by prayer and is done for a specific purpose. Just do a simple word search and see for yourself.

Yet while we have had this needed corrective to the concept of fasting, we have not yet replaced it with a helpful, positive view of what fasting should be. This is what I want to explore for a bit in this article. Secondly, I want to explore whether this new reformed kind of fasting has a place in Lent.

What then is fasting for, and when should we do it? In the Bible people always fast for a specific purpose, and fasting is always coupled with prayer. Therefore, you never find a person in the Scriptures fasting as a general spiritual discipline. There is always a reason for the fast. People in the Bible fasted when they wanted an answer to prayer.

Furthermore, there is a strong connection in the Bible between fasting, mourning, and repentance. I will give two examples of this from the book of Samuel. In 1 Samuel 7, the people were oppressed by the Philistines and longed for deliverance. Samuel, now Judge of Israel, calls the people to put away their idols and repent of their sins so that Yahweh will deliver them. The people then respond to Samuel by obeying his word, and then in verse 6 we find that they fast and pray as a sign of repentance and also to ask Yahweh to deliver them, ” So they gathered at Mizpah and drew water and poured it out before the LORD and fasted on that day and said there, “We have sinned against the LORD.” And Samuel judged the people of Israel at Mizpah.” So the people fasted as a sign of repentance and the Lord delivered them from the Philistines.

Another example of this is from the life of David in 2 Samuel 12. After David commits adultery with Bathsheba and is called out for his sin, he repents of it. Still, as a result of David’s fall, Nathan says that Yahweh is going to take his first son by her. When the child becomes sick (the text says that Yahweh afflicted the child) we find this in 12:16, ” David therefore sought God on behalf of the child. And David fasted and went in and lay all night on the ground.” Again, we find that fasting is coupled with mourning, repentance, and a request for deliverance.

Example after example from the Scriptures can be brought forth in support of this general idea. What the biblical data shows us is that we fast when we are in a very serious situation. We fast when we are mourning and asking for deliverance. We fast when we are penitent. We fast as a physical manifestation of our urgency in crying out to God to hear and answer us in our time of need.

The criticism of fasting in the Bible that we find from Jesus and the prophets is not that it is a bad practice, but the criticism is that it is not done in a sincere way. The Old Testament reading for Ash Wednesday in the Book of Common Prayer is Isaiah 58:1-12. In that text the fasting is performed in an outward but insincere way. The text continues that fasting must be coupled with acts of righteousness. It must be accompanied by true contrition. Outward acts alone are not enough, but they must flow from the inward condition of the heart.

Given this, should a Christian undertake regular times of fasting, or should it be irregular and infrequent? Ask yourself: is the church called to sacrifice itself for the life of the world? Do we take seriously our call to die to self? Is it just when circumstances in my own life are bad that I should mourn and fast, or should I, we, the Church, fast and mourn on behalf of our broken, fallen world, asking for our God to deliver it from evil and for His Kingdom to come? Do we not see enough reasons around us to fast and mourn for the deliverance of our city? Our nation? Our world? Do we have our eyes open?

Perhaps we should view fasting as a type of memorial like the Lord’s Supper, though to a lesser degree. In the Scriptures a memorial is something that primarily serves to remind God, and only secondarily serves to remind us. A good example of his is the rainbow. In Genesis 9:13-15, God tells Noah that he will set the rainbow in the clouds to be a reminder to Him, and that when God sees it, God will remember his covenant with the creation not to ever destroy it again by a flood. Of course, since the rainbow is a physical sign that we can also see, we are also reminded of God’s promise when we see it, yet it is primarily to remind God. In the same way, the Lord’s Supper is a memorial, and when we celebrate the Lord’s Supper we are primarily reminding God of his covenant promises to us, and only secondarily reminding ourselves of Christ’s death on our behalf. Nevertheless, the two, God’s remembering and our remembering, are inseparable.

In the same way, the Bible also speaks of prayer as a memorial. One clear example in Acts 10:6 where God appears in a vision to Cornelius the gentile and tells him that his prayers and his alms have ascended as a memorial before God (see also Acts 10:31). As a result, Cornelius is to send for Peter who will preach the gospel to him and his household. As we know, Peter comes, he preaches the gospel, and the Holy Spirit falls on the gentiles assembled there as He did at Pentecost. Then Peter baptizes all of them.

Now my point in mentioning this is that twice in this account by Luke, in verse 6 and in verse 31, prayer is called a memorial, and it is clearly a memorial that reminds God. In the same way we can see fasting as intensified prayer and that fasting too is a kind of memorial, a sacrificial offering that ascends to the Lord and gets his attention. Now this may raise our hyper-calvinist hackles, but this is the way the Bible speaks.

Therefore if prayer is a memorial and fasting is an intensified type of memorial prayer, then we can see why the church would want to enter into regular periods of prayer and fasting for the sake of the broken world around us. We are called as the church to take up our crosses, deny ourselves, and follow Jesus; follow Jesus into the wilderness; follow him as he gives his life for the life of the world. Lenten fasting is one small way in which we follow Christ by offering up our memorial before the face of God, asking him to act on our behalf.

Therefore what are we fasting and praying for in Lent? We are mourning and fasting because of our own sins. We are acknowledging our part in the broken condition in this world, and we are calling on God to act in our lives to heal us of our own sinfulness and to help us to lead lives of righteousness. Furthermore, we are fasting and praying for the life of the world. We are crying out to God to come and fix our broken world, and we are denying ourselves as a memorial before his face that he will act to strike down evil and cause his kingdom to come in evermore increasing ways in this world. In this way, Lenten fasting is a sacrificial act by the church on behalf of our world. Through it we are crying out to God to fix all the brokenness and pain we see around us: all the death, the sin, the wickedness, the injustice, the poverty, the disease, the war, the infertility, the loss, the hurt, the loneliness – every single way in which this world is fallen and broken – we are crying out to God to heal, to save, to deliver.

So, you see, we do have reasons to fast during Lent. We have good biblical and theological reasons for our fasting and abstinence. Through our fasting we are acting as living sacrifices, living memorial stones, asking God to heal our world, a world that we can surely seen is in desperate need of His healing touch.

Dr. Timothy LeCroy is a Special Contributing Scholar to the Kuyperian Commentary and is the Pastor of Christ Our King Presbyterian Church in Columbia, MO.

A final post is planned which will address abstinence, otherwise known as giving up things for Lent.<>